The official launch (online event) of the book entitled “Indigenous Peoples’ food systems: Insights on sustainability and resilience from the frontline of climate change” published by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the UN and the Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT was held on June 25, 2021. This book analyses eight different Indigenous Peoples food systems in Asia, Pacific, Latin America, Arctic and Africa identifies threats affecting their food security and warns about their future and the impacts their disappearance will have on humanity’s ability to adapt to climate change.

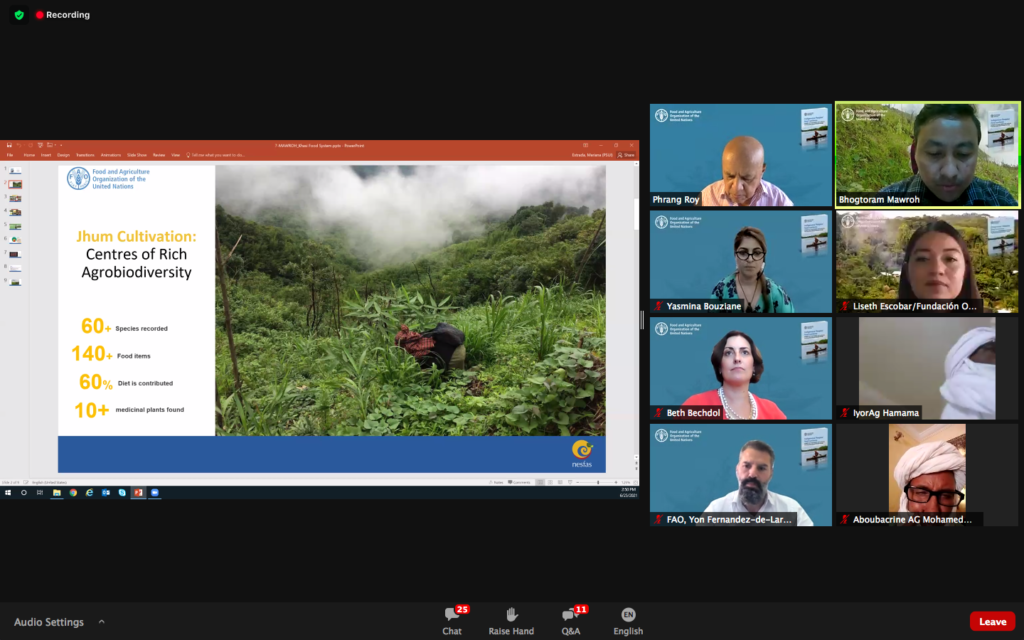

The study area was in the Nongtraw community, facilitated by NESFAS and TIP. It highlights the centrality of Jhum cultivation, a rotational form of food generation and production. Dr Bhogtoram Mawroh PhD, Sr. Associate, NESFAS, and co-author of the Khasi Food System chapter, presented the key findings during the event. The study shows that more than sixty per cent of the food produced is from Jhum cultivation, which has enabled the communities to attain autonomy in food production. A major percentage of the diet and income comes from the Jhum-based Indigenous Food System (IFS). The study also records that more than sixty species of food plants were found in Jhum cultivation. Other key findings include the role of women, which has seen to be prominent for many years in the process of food production.

The chapter for the Khasi Food System is titled “Treasures from shifting cultivation in the Himalayan’s evergreen forest- Jhum, fishing and gathering food system of the Khasi people in Meghalaya, India”. This chapter was authored by community members of Nongtraw village, Meghalaya, India, NESFAS Team members and Associates, which included Bhogtoram Mawroh, Ruth Sohtun, Pius Ranee, Melari Nongrum. Phrang Roy, Coordinator, TIP and Founding Chair, NESFAS, along with Gennifer Meldrum, Alliance of Bioversity International and CIAT, Rome, Italy.

This magnificent book is a compilation of 398 pages with a total of eight Chapters by renowned authors, academicians and researchers in the field. The book had a brief ‘Policy recommendations at the beginning, which vary from rights to land, multifunctionality of the systems and self-sufficiency, continuity of traditional practices, Governance, youth, education systems, to Globalization and the drivers of sustainability for the eight Indigenous Peoples’ food systems.

Chapter I highlights the ‘Hunting, gathering and food sharing in Africa’s rainforests’ (The forest-based food system of the Baka indigenous people in South-eastern Cameroon), Chapter II talked about the ‘Voices from Arctic nomads: an ancestral system facing global warming (Reindeer herding food system of the Inari Sámi people in Nellim, Finland), Chapter IV is entitled ‘From the ocean to the mountains: storytelling in the Pacific Islands (Fishing and agroforestry food system of the Melanesians people in Solomon Islands). Chapter V is on ‘Surviving in the desert: the resilience of the nomadic herders’ (Pastoralist food system of the Kel Tamasheq people in Aratène, Mali). Another study which is from India is Chapter VI entitled ‘Ancestral nomadism and farming in the mountains’ (Agro-pastoralism and gathering food system of the Bhotia and Anwal peoples in Uttarakhand, India). Chapter VII is about ‘Following the flooding cycles in the Amazon rainforest’ (Fishing, chagra and forest food system of the Tikuna, Cocama and Yagua peoples in Puerto Nariño, Colombia) and Chapter VIII is on ‘The maize people in the Mesoamerican dry corridor (Milpa food system of the Maya Ch’orti’ people in Chiquimula, Guatemala).

Finding solutions to climate change is not just a priority, it is an emergency opines Anne Nuorgam, Chair of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII). “This all-encompassing richness in culture and traditions allows Indigenous Peoples to develop and sustain diverse and unique food systems. From reindeer herding to gathering wild plants and berries, Indigenous Peoples generate and collect food in complex, holistic and resilient ways whilst always respecting the need to preserve the biological diversity that generates and maintains harmony in nature. Eating and feeding but without destroying. Eating and feeding but maintaining biodiversity. Eating and feeding thanks to Mother Earth’s generosity that needs to be nurtured, protected and respected”.

“Indigenous Peoples’ wisdom, traditional knowledge and ability to adapt provide lessons from which other non-indigenous societies can learn, especially when designing more sustainable food systems that mitigate climate change and environmental degradation. We are all in a race against time with the speed of events accelerating by the day. It is crucial to recognise Indigenous Peoples as key players in achieving the 2030 Agenda and to create larger spaces for more inclusive dialogues recognising the vast lessons to be learned from them”. While reflecting on the right of the indigenous population globally, it further mentions Indigenous Peoples hold internationally recognised rights for the preservation of their food systems through the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), particularly through the inherent right to self-determination and their right to food”.

“The right to food of Indigenous Peoples was also recognised in the 2004 Voluntary Guidelines on the Right to Food, indicating how these rights are strongly linked to Indigenous Peoples’ lands, resources and culture. Therefore, human-rights-based dialogue is necessary to ensure the inclusion of Indigenous Peoples in global debates on ending hunger and ensuring food security for all”. (Extract from the Forward of the Book).

Chapter III which is a highlight of this write-up is divided into 3 sections. Section I is about the Community and Food System Profile. Section II is about the Sustainability of the Indigenous People’s Food System and Section III is on the Conclusions and Future Projections. This initiative is believed to “help policymakers around the globe to customize their own policies on food for sustainable development”. Dr Mawroh, one of the co-authors expressed that, “North East India and Meghalaya in particular still maintain strong indigenous food systems. However, this is coming under increasing threat. The study helps in shedding light on the sustainability of the Indigenous Peoples’ food systems and bringing out lessons for resilience and sustainability of the food systems in general”.

NESFAS which has put up a lot of effort in bringing about this chapter in the Book through its team members is honoured to be one of the few indigenous organisations from around the world that is part of this global study. A key takeaway from this study was that severe food insecurity is non-existent, and Nongtraw being one of our strong partner communities has come out as an example to demonstrate that indigenous food systems, such as the Jhum cultivation, have a very important role to play in achieving the target of Zero Hunger.

This chapter consists of 44 pages. The work put into this document is comprehensive and has been able to highlight some of the most prominent food practices of the indigenous people in this region. Phrang Roy, one of the co-authors has rightly stated that “Our Indigenous Food Systems (IFS) are determined by self-determination and values of sharing and caring”, shared. IFS can be a game-changer because it is evident in the Nongtraw community, which upheld strong social, cultural and spiritual values in their food system and well-being.

On a lighter note, the take away message from this chapter shows that “The community also believes that being able to maintain and sustain their traditional farming practices by avoiding fertilizers and pesticides is one of their greatest strengths. Agriculture offers a way for community members to interact and connect with one another, allowing them to help each other in times of food insecurity and sharing/exchanging of seeds and food within the village. The traditional knowledge regarding the food system is still being passed on to new generations”.

This article is also published in The Meghalaya Times

Translate

Translate