Mawpynthymmai: An hour away from the road, sitting at the foot of a hill, lays this small community of 23 households. In 2008, a group consisting of three families moved away from their original community to the hill which lies opposite to theirs to start a new community with new mindsets and new beliefs.

Mawpynthymmai is a community that started with three households in 2008 and in a year, increased to 10 households where it is now rich and comfortable in its resources. Jingimmisda Pyngrope (62) who helped pioneer their new community, is a knowledge holder and helped shape the community into what it is today. Jingimmisda described her journey as one that is filled with new thinking, new values, and new beginnings; that is also where the community got its name from. She said it takes careful consideration of whom they lead into the community. The community has also learned to keep their corners clean by reducing their plastic footprints and non-recyclable products. It also depends on solar energy to power the entire community.

She said, “NESFAS has brought many changes to this community; the importance of keeping our community clean and sustainable are the two most important things we as a community have learned.” “The kitchen gardens have helped us be more aware of our local foods. Earlier we would eat anything we find but NESFAS has helped us picked out food which will give us nutrition and value,” she added.

This community, being such a small one, has one structure for all of their community work, as well as their school and the church. This community hall sees the day-to-day activities of the school-going children and at the end of the day, the community gathers to matters that need to be attended to. The school had initiated the school garden after the intervention by NESFAS to help the children learn about the importance of local indigenous food systems and how to work for the environment.

The school garden was started after the training by NESFAS, under the Rural Electrification Corporation Foundation (REC)-funded project ‘No One Shall Be Left Behind Initiative’, to help the children to be more aware of the local food systems and to be more in touch with the environment. This initiation has taught the school going children teamwork, cleanliness, and a sense of purpose to preserve the indigenous food system. The school garden was set up in 2020 with the hope to revive the local food systems and wild edibles at the community. The school garden sees the participation of all the school going children who share their love for food with the community especially for the pregnant women and children. As winter approaches, the school garden farms only sweet potato as their source of cultivation.

The community’s general secretary, teacher of the school, and community facilitator Aijingshai Pyngrope helps the children utilize their resources by teaching them the importance of the school garden. Through his efforts, he gathers the school children’s parents to help set up this task as the community mid-day meal mission.

Further, Aijingshai credits NESFAS for its impact on influencing all 23 households in the community to start their journey with kitchen gardens. The communities empower a chemically free and sustainable approach to farming. The kitchen gardens have also helped remind them of the old traditional ways of farming specially to crops such as millet. The community sees the productivity of crops such as banana, tea leaves, yam, sweet potato, mulberry, oranges, sugar cane, and lemon.

Thwirenglist Pyngrope (50), a community member, was one of the first to kick off the kitchen gardens. Before NESFAS, the community would purchase products from the local market but now, they depend on their own kitchen gardens. The local food is nutritionally sourced and help give strength, especially for the pregnant women and sick community members. She grows in her garden green leafy vegetables such as jaut, jali, chameleon plant (sla jamyrdoh), sweet potato leaves (sla phankaro), and mustard leaves. Besides that, she grows tree tomatoes, sweet potato, ginger, radish, lemon and yam.

Thwirenglist said, “Earlier we would not plant many varieties of crops in our backyard. We did not know so much about indigenous farming but now we have been introduced to so much hope of preserving and reviving the indigenous food systems.”

NESFAS also played a role in providing seeds to the communities such as corn, beans, millet, mustard, and radish. When the community members have guests in their houses, they would feed them products purchased from the market, however, now that the kitchen garden provides a wholesome variety of produce, the community members now feed their guests with snacks found in their backyard.

The household in the community has also used the innovative methods of their own intervention to produce their crops by creating a shallow pool of water around the soil to hold moisture for the crops in the winter. Iriang Nongrum (35) and Wallamjingkmen Pyngrope (36) use this method to keep the moisture in the soil and used bamboos to close the dwelling.

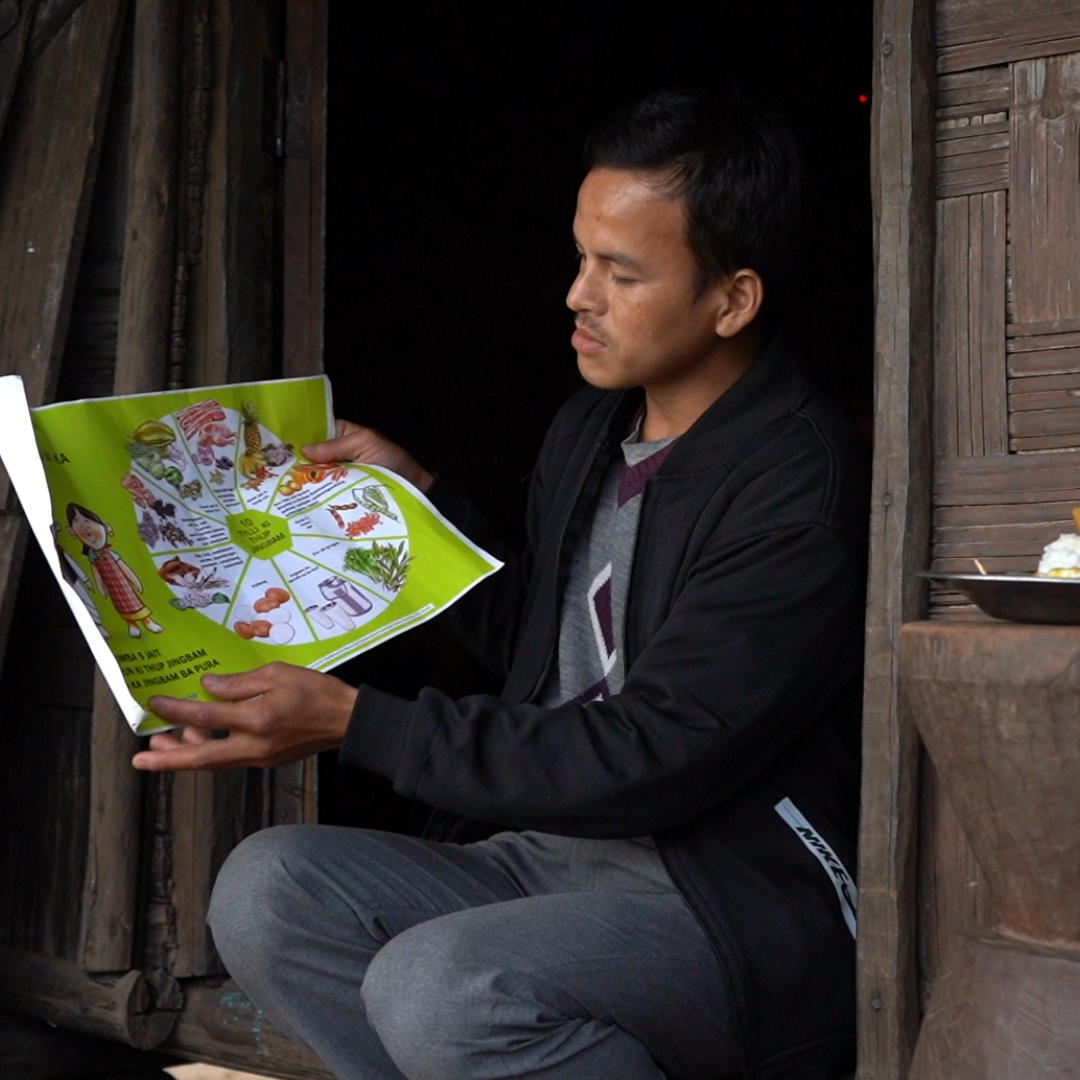

Ladappura Pyngrope, former community facilitator of NESFAS, was the pioneer in training the community on the importance of indigenous food systems and introducing the 10-food group into the community. To share knowledge and ideas was the key to a rich and flourishing community. The community has changed their marketing habits where they no longer depended on the local market for their produce but their own kitchen gardens.

The community also prospers in beekeeping. The community began beekeeping bees known locally as nangtam as a means to earn living; the community members brought the bees in from the forest and harvest a chemically free honey for the market. Wallamjingkmen Pyngrope, the community headman and one of the 11 beekeepers of the community said beekeeping was a way to help the community. This year has been a difficult year for the beekeepers as the monsoon had halted the work, especially in producing honey.

At the end of the day, this community only wants to see other communities to prosper like they have. They are ready to share their seeds with other communities and exchange knowledge. They hope that they can be an example to other communities at how they have so readily welcomed the idea of kitchen gardens. In the future, they hope that when a natural disaster hits such as the present pandemic, they would be ready and give space to those who are not.

Translate

Translate